“According to the researcher Vera Malguti, the public enemy number one is being sculptured after a model which is the grandson of slaves, who lives in favelas, doesn’t know how to read, loves funk music, consumes drugs or lives from them, is arrogant and aggressive, and does not show the least sign of resignation.” – Eduardo Galeano

In the picturesque, tropical city of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, violent crime is recognised as one of the most important contemporary, armed with blood-shot eyes and weapons that seem like things out of a desert battlefront, and episodes of warlike confrontations in the streets has made the city notorious, both nationally and internationally. The military police are known to be ruthless and corrupt, making alliances with gangs at the same time as they raid favelas, the marginalised neighbourhoods often called “slums”, all guns blazing, leaving corpses in their wake. All the while, residents of favelas try to work, play and live in a situation of continuous insecurity. Most dream of peace, social inclusion, and economic improvement. Recently, they received new hope in the form of a new police strategy designed to put an end to the reign of traffickers as well as further social inclusion. In 2008 the communitarian UPP or Pacifying Police Unit project was implemented in the first favelas. The idea is that after traffickers are forced out of the areas by elite squads of military police and the army, specially trained police officers establish bases within the neighbourhoods, and thereafter the construction of schools and hospitals are supported by the government. The UPP has been celebrated nationally and internationally for its new vision of how to handle gang control in peripheral areas, with a realistic approach to bringing peace to vulnerable urban populations. As Rio became the host of both 2014’s FIFA world cup and the RIO 2016 Summer Olympics, the strategy has been the flagship of public security policy in Brazil. However, the strategy has been criticised, primarily by residents, activists and researchers, who claim that UPP does not alleviate the casualties of police violence, increased gentrification and thus displacement of the already vulnerable, and does not bring the social infrastructure it promised.

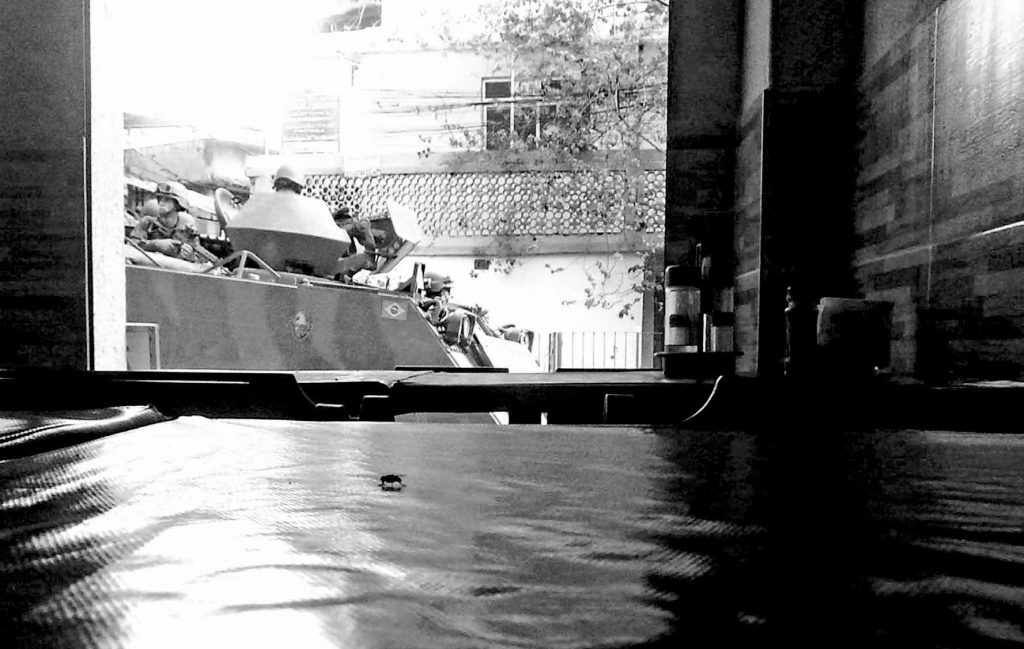

The UPP has never really moved beyond the occupation of an area called Maré, a “cluster” of 17 neighbourhoods in northeastern Rio, populated by around 140,000 people. In 2015, I lived in the area for four months, to research how residents experienced the new strategy, and to ask what change they saw in their everyday. Here, the residents spoke of a “false”, “invented”, or “unequal” war waged against them, where their homes become front lines in a battlefield. While they refused to give up their daily struggle to live a normal life, they found it more and more difficult to avoid being caught in the crossfire. War tanks patrolled the streets and soldiers in full combat gear stood guard by entrances, street corners, and public squares, next to children playing football and families having barbecues. Some residents felt that the politics were of extermination rather than social inclusion, since they were seen as enemies instead of civilians.

The war on drugs and the war of drugs

The reason for the situation is on one hand what we could either call the war on drugs or the war of drugs. Since they first emerged in the beginning of the 20th century, favelas were built and populated by the urban working poor and internal migrants in search of better opportunities. Property owners found it extremely lucrative to sell informal property titles, while employers, such as factories, deemed it cheaper to allow the workforce to construct nearby shacks rather than house them officially. Today, there is around 900 such neighbourhoods loosely defined as favelas all over the city. Public negligence has meant that infrastructure such as schools, hospitals, and bus lines are scarce, while residents and short-lived projects have built electricity networks, sewers, paved streets and have transformed most wooden shacks into three- or fourstory brick houses. Their peripheral, but central geography made them favourable territory for drug gangs, and by the 1990’s favelas were dominated by organised crime, who packaged and sold marijuana, cocaine, provided some state-like services and protection from other gangs. Three major gangs compete for control over the market: Comando Vermelho, “The Red Command”, Terceiro Comando, “The Third Command”, and Amigos Dos Amigos, “The Friends of Friends”. This competition meant that eventually in the mid-90’s, violence began to spill over into the rest of the city, and the public demanded security and a response. The reaction came in the form of extremely violent police incursions, which in turn provoked the traffickers to buy even heavier weaponry. Inspired by U.S.A.’s “War on drugs” and no-tolerance policies, almost all research has shown that such an approach to public security has very little effect on actually diminishing drug-related crime and its victims, while it serves brilliantly to marginalise poor and peripheral urban populations.

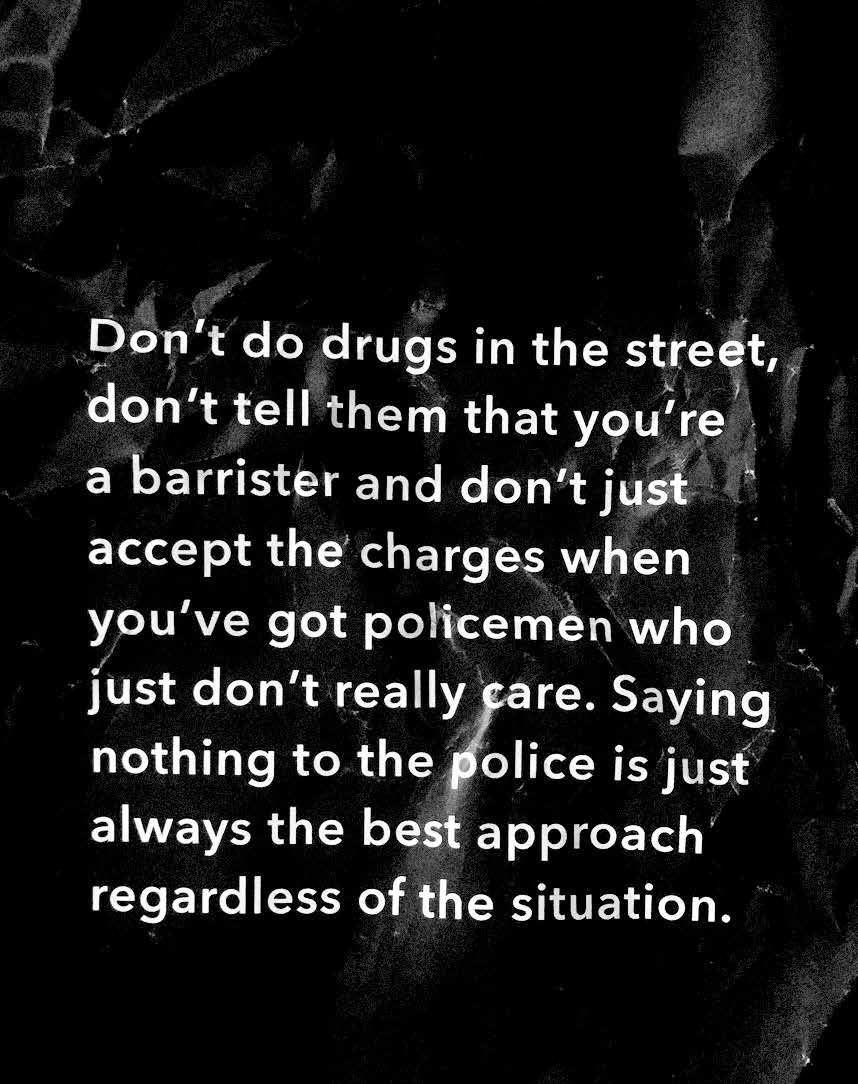

It’s a public secret that police and traffickers do business on a regular basis, and that companies and politicians are involved on different levels. There’s a lot of money to be made by supplying Brazilian society with recreational drugs. At the same time, the sensationalist media paints brutal images of crime and fetishises the iron fist of military-police action, justifying if not even encouraging the extra-judicial killings of favela populations.

A nervous community

As mentioned, the UPP project was established to attempt to reverse the vicious cycle of hard-handed police incursions, and generally further disarmament. This has not been the case in several of the larger favela areas, where UPP has been implemented. It’s increasingly clear now that the question has more been one of making sure that the troubled neighbourhoods were contained, while the world’s eyes were fixed on Rio. My friend Maria, resident and journalist in Maré, was sure that the UPP would not last longer than the Olympics, and that Maré would continue in a state of military occupation. “It will be pretence that the city is safe because the marginals and the favelados, the bandits as well as the residents, they will all be here in their place. After this they will disappear and say that they do not have enough money and police officers to pacify Maré”, she told me in her apartment in April 2015. Tellingly, the military and police invaded the area one month before the FIFA world cup in 2014, and this year Rio’s secretary of security, José Beltrame, said that “the UPP in Maré will not be made” before 2017 at the earliest.

During the time I lived in Maré, it became increasingly clear that the UPP, as a communitarian police project, had failed. Instead, it was more militarised urbanism, which increased daily existential uncertainty for residents and did not have an impact on the number on primarily young, afro-Brazilian men killed by police and in trafficker shootouts. When insecurity rose, so did suspicion, and therefore my efforts to document the situation in photographs became difficult. I could almost only take pictures with no people in them, as when people stayed off the streets after military actions or drug-related shootings. These pictures thus resulted in strangely devoid, uncanny scenes of an otherwise lively community. This is yet another example of the local consequences of the global war on drugs.