Niclas is sitting on a chair in a waiting room. We’re in a heroin rehab center in Odense, a medium-sized Danish city, known to tourists as the birthplace of poet and adventurer Hans Christian Andersen, but for most Danes as just another freeway exit one passes when crossing the country.

There’s cake, a coffee machine, an aquarium and some computers with internet access on which a woman is trying to buy tickets for a Bruce Springsteen concert while a man is watching youtube videos of Russian bikini babes. Hanging on the walls are advertisements for programmes to help people quit smoking as well as a bulletin board containing notes requesting more classes in line dancing and further bowling outings. Niclas is wearing a dusty, green parka coat even inside the center, but he doesn’t care right now, because he’s feeling great. He leans his head forward, looking down at the table, so that his long, tangled hair covers his face. The heat migrates up his vertebrae and he experiences a tightness in the neck that most of all resembles inner chills. He finds himself in the state one is in just before going to sleep—the borderland between dream and reality—while loud music is playing in his earphones. This is the place where all the junkies go where times get fast but everything gets slow (Red Hot Chili Peppers). The room is now a large painting by Jean-Michel Basquiat: Filled with yellow, orange, red, blue and green neon colours and black, half-dead, creepy people, who make childish gestures, laughing all the while. The thing is, I am here with Niclas because I want to understand what it feels like to be so addicted to a substance that the feeling you get from it overrides everything else in your whole life. I thought my article would be about sweating, diarrhoea and dripping noses, but Niclas is not injecting himself to avoid withdrawal symptoms. Nor is it because he wants to feel the chills or get lost in his dreams (those are just positive side effects). No, he puts a needle in his veins in order to become the person he would most like to be. Like Jimi Hendrix or Keith Richards or even just Niclas Christiansen, a confident, musical rebel. “One thing that addicts have in common is that they want to be [drug] abusers,” Niclas explains, which is why this article will focus more on him than on the drugs themselves.

Niclas is currently unemployed, but three years ago he made an album with his younger brother and a couple of friends. Calling themselves The Road to Suicide, they played ‘60s inspired rock music without synthesisers but with a lot of noise. The band performed in Copenhagen, as well as a few places on Fyn and in Aarhus, and they sold a lot of vinyl—considering they were a shitty little band. Niclas was the lead singer, wrote the lyrics and played the guitar, and it was here he found out that heroin could do something magical. For a time, he bought a little bit every day, which he took home and injected in his room before starting to write. And the music flowed from him in a stream of consciousness as if he were the author Jack Kerouac at his most doped up in front of the typewriter. Or maybe he was just like Jim Morrisson — all right, except that he was sitting in an apartment in Odense and not in a room at the Chelsea Hotel in New York City. “If the doors of perception were cleansed everything would appear to man as it is” — William Blake

Heroin was just fucking with him, he remembers. “I have always been good at playing music. I thought that was the only thing I was good at, until I found out that I was also good at doing heroin,” he says. Unfortunately, just a few months later he had a panic attack during a nap, and the drugs became necessary for Niclas to find peace. He always performed on heroin or Suboxone, but when the band was offered the opportunity of a lifetime, Niclas bailed out with only six hours to spare. The Road to Suicide was going to London, but Niclas could not figure out how to make it work either with or without the heroin. When one travels by boat it’s hard to bring along drug paraphernalia. And that was what’s called a life changing moment. The band broke up, and from that day on Niclas was slightly less a musician and a little bit more of a junkie. But still one hell of a rebel.

Now, the days look alike and have done so for the past few years. After paying a visit to the rehab center in the morning, Niclas goes back to his one-room apartment and usually lies down on his old, red couch. He likes reading books, an erotic tale at the moment, but his favourite author is the beat writer and junkie poet William S. Burroughs. He really digs Burroughs’ surreal universe and his descriptions of modern society shot through with violence, sex and drugs. It’s just that he often ends up reading the same lines again and again and again. Eventually, he loses focus and instead just gazes at the Persian rug on the floor. Scattered around the room are his six guitars that he practises on from time to time. On good days, his friend Peter drops by for a cup of coffee, before Niclas has to go back to the rehab center in the afternoon. Peter and Niclas have known each other since they were twelve years old, and Peter has never disapproved of his drug consumption. Niclas doesn’t see anybody from the band anymore except for his younger brother and a single phone conversation with the drummer. But Niclas still has a friend whom he occasionally accompanies to the rehearsal studio. He hopes he will continue to be invited, so that one day he might again be given the choice between music and heroin and this time choose correctly.

Because Niclas still believes in another future far from the treatment facility—but with a lot of guitar playing. In fact, he thinks music is the only thing that might get him to stop using. “I’ve tried to stop because of my guilty conscience towards my family, friends and girlfriend, but it just doesn’t cut it. It has to come from within me. If I knew someone who could get me to quit heroin, I would have done it long ago,” he notes. “I thought I could pull a Lou Reed. But it was probably a stupid and naive thing to think, before I had gotten anywhere in my life.” It also seems to be the conviction of the friendly nurse at the rehab center with whom I chit-chat a little. “We have told Niclas that it is not appropriate to cultivate a fascination of the drug universe,” she said to me in a digression. I assume she means inappropriate if Niclas wants to get rid of his addiction, but I don’t understand it completely. Because Niclas doesn’t just cultivate a fascination with drugs. He cultivates a fascination with the musicians and rebels of the ‘60s as well as their poetry and art. And he cultivates himself as he is. And if this gives him hope for a life outside this rehab center, then why suppress it? Is there really anything left of Niclas if he throws out his parka coat, cuts his hair, burns his books and sells his guitars? He may be sitting on the siding, but he is not stuck there. He just takes a long time to switch tracks.

You cannot brand me, not you guys

All you sweet girls with all your sweet talk

You can all go take a walk

And I guess I just don’t know

(Velvet Underground)

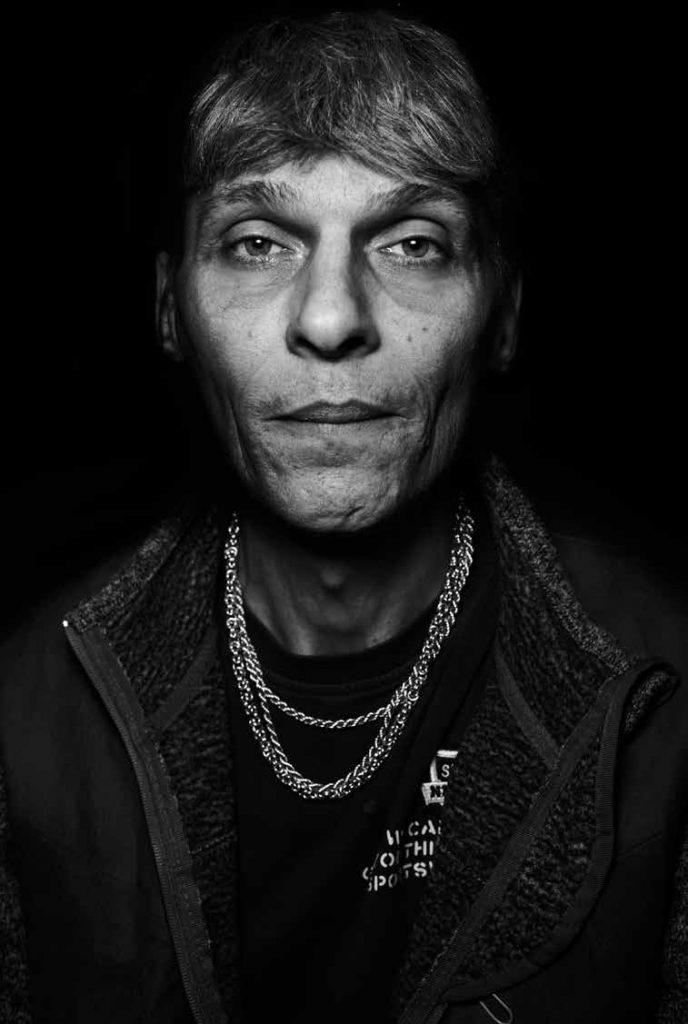

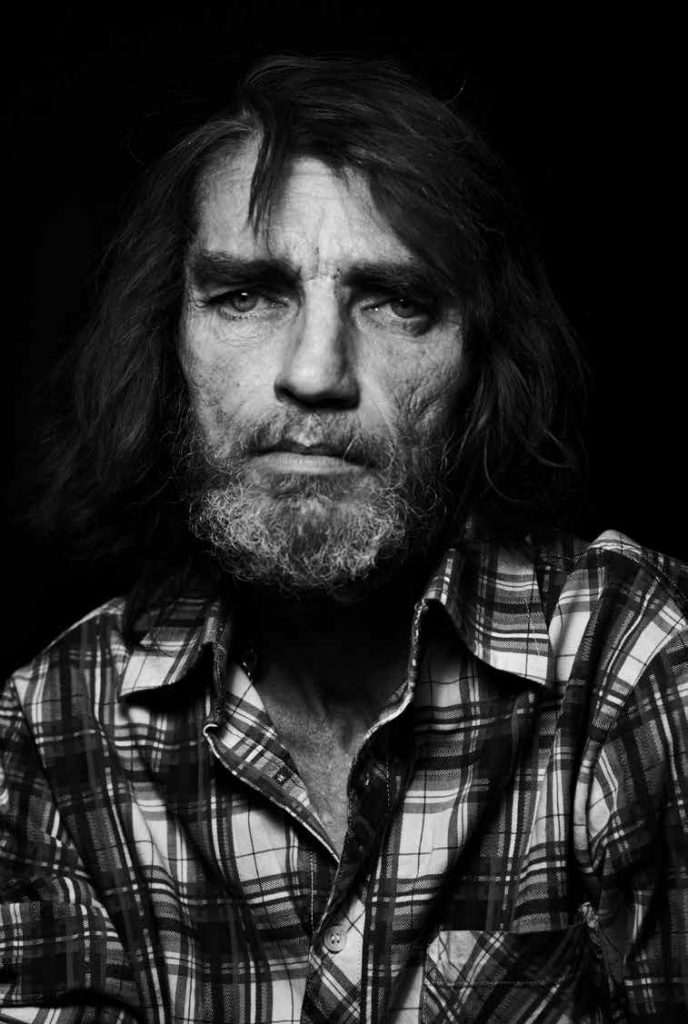

‘Heroin’ is a series of portraits by photographer Marcus Trappaud Bjørn.

The series captures the moment just after injection when the drug reaches the brain, withdrawal symptoms disappear and the rush kicks in. The moment that controls the lives of the people addicted to heroin. The portraits are calm, clean and leave out all the elements that are normally associated with heroin. No blood, no tourniquets, no syringes, no needle marks. The viewer is allowed to experience an undramatic and beautiful moment that challenges the perception of how heroin users are normally presented in the media.