I’d like to share some information concerning the likely psychedelic origins of some well-known cultural phenomena in the European and Middle Eastern cultures. However, I begin with reservations about the following hypotheses, some of which aren’t scientifically substantiated. On the other hand, quite a few things taken as given by academia aren’t proven fact, scientifically speaking. And perhaps to no great surprise, since academic subjects such as history, archaeology, anthropology, ethnography and ethnology aren’t exactly exact sciences, to which countless foundered theories in these fields attest. So a lot of the handed-down knowledge in these subjects actually consists of presumptions and more or less qualified conjecture—just like this presentation. So please take the following with a grain of salt.

The Witch’s Broomstick

Nowadays, the myth of witches flying to Sabbath on their broomsticks is widely rejected as just so much superstition. Which it is, taken at face value, but the myth likely has its roots in real practices, the aim of which was indeed to “go flying” by means of a psychotropic “flying ointment”.

Unfortunately, knowledge concerning the exact recipe, administration and effect of these ointments is limited, for even back then it was a well-kept secret. The Inquisition had certain information brought to light but didn’t seem very interested in this aspect of the matter, besides which, information obtained by means of torture is notoriously unreliable.

Nonetheless, a broad consensus exists concerning the following: The witches’ ointment probably contained one or more of these plants: belladonna, black nightshade, mandrake root, henbane, datura seeds, cowbane, hemlock, iris, water lily, winter aconite, toxic ryegrass, splurge, and maybe even opium poppy and the liberty cap. The ointment must have been fatbased, because an ointment dating from the 12th or 13th century has been found which consisted of 40% animal fat. This makes good sense, since the fat would facilitate the absorption of psychoactive alkaloids of the plants through the mucous membranes and the skin.

Some of these plants are quite poisonous, and one must be extremely careful ingesting them so one doesn’t die or roam around in a state of delirium for several days. That’s why the witches applied them externally, which is to say that the plant ingredients were mixed together in an ointment that was absorbed through the mucous membranes. The method of ingestion consisted in coating a broomstick or something similar with the ointment and then inserting it into the vagina or anus or the groin or armpit—the former being a more effective means of delivery than the latter—and soon after a state of trance was achieved.

Suddenly, the myth of witches flying about on broomsticks makes a bit more sense. An alternative way of ingesting the plants, by the way, is to put them in a foot bath, but you can’t very well burn an effigy of that and, moreover, the sexual connotations would be lost, which would be a great shame, a point of view I’m sure the witches themselves would share.

Furthermore, a related symbolism may be at play here. Myths about the witches often contain an element wherein the witch leaves her house on a broomstick through the chimney. Put in historical context, this can be seen as a symbolic escape.

After the Reformation took place in the 16th century, women’s lives were increasingly confined within the four walls of the home and their roles as mother and wife, compared to, say, 200 years earlier. Thus, the skyward escape of the witch through the chimney can be interpreted as an escape from the home and the chains of the stove—perhaps even from patriarchy itself, with its constricting shackles of piety, monotony, monogamy and misogyny. But that’s another story.

The Flying Carpet

From the witch’s broomstick, we adroitly hop on board the flying carpet. From where does this tall tale really stem? Well, the mythology of the Middle East, obviously, but, like so many other elements found in One Thousand and One Nights and similar texts, there’s probably more to this phenomenon than idle daydreaming.

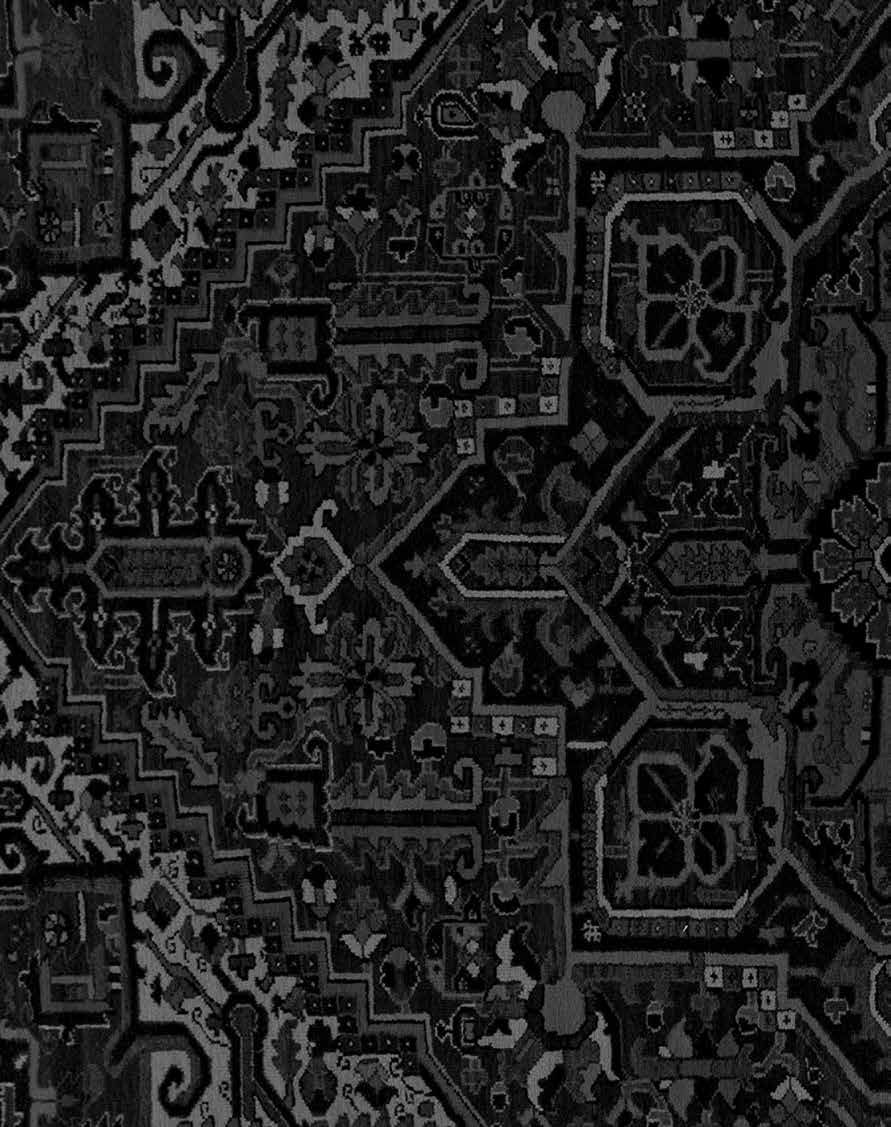

So let’s have a closer look at how carpets were made in Persian and Arabian antiquity, and specifically how they were dyed. For this purpose, the seeds of a plant called Peganum harmala were utilised.

A perennial plant of the family Nitrariaceae, it stands about 0.3 meters tall and carries white flowers. The round seed capsules measure about 1–1.5 cm in diameter, have three chambers and carry more than 50 seeds from which the dye Persian red is extracted and used to dye fabrics, e.g. carpets. Moreover, Nitrariaceae has been used since antiquity as a panacea for such different ailments as Parkinson’s disease, rheumatism and low spirits, and as incense and an aphrodisiac.

But if a sufficient amount of the alkaloids contained in the seeds are ingested, orally or through the skin, they are also psychoactive. At lower doses, a dreamlike state is induced, while at higher doses humming noises are heard and one’s surroundings billow in addition to a feeling of both sinking and flying simultaneously. A common denominator of harmala-induced hallucinations is highly detailed, geometric patterns not unlike certain carpet designs.

This is why it is believed by many that the myth of flying carpets was conceived by the people who extracted dye from harmala seeds and used it to decorate carpets. When one entered the harmala trance, one sat down on one carpet and gazed upon another hung on a wall. Having thus gained access to the spirit world, one could navigate in it by focusing on the different areas of the carpet that in turn corresponded to specific places in the spirit world.

Another popular hypothesis is that harmalahallucinations were the source of inspiration for the all the fantastically detailed, almost hypnotic patterns swirling through the architecture and artwork of Islam.

A third concerns itself with the whirling Dervishes, Sufi mystics who obtained ecstatic visions through their trademark whirling dance. And perhaps also from the harmala dye in their faeces, macerated in the feverish sweat from their brows and absorbed through the temples.

An even bolder speculation explores the possibility that mystics like the Sufis mixed Peganum harmala with a plant containing the hallucinogen DMT. For if you do that you end up with an analogue to ayahuasca, the notorious jungle brew from the Amazon, which, if ingested, should ensure an exorbitant amount of revelations and hallucinations.

Regardless of this being the case or not, it’s an established fact that this little herb has been favoured traditionally all over the Middle East, especially in Shia Muslim regions, both as a source of dye as well as a medicine and an intoxicant. It is praised in Persian poetry and is even mentioned in the Hadiths, a collection of interpretations of the Koran.

Some even believe that Peganum harmala could be the mythical drug soma, which plays a central role in both Hinduism and the ancient Persian Zoroastrian religion, in which it is known as haoma. That is all for now, but you can read all about Santa’s mysterious origins in the next installment.

Santa Claus

From the soaring minarets of Persia, the flying carpet now takes us way up north to get acquainted with Santa Claus and his flying sledge, who may have more to do with shamanism and psychoactive mushrooms than immediately apparent.

Santa Claus and many other Christmas traditions seem odd and out of place in the celebration of the birth of the king of the Jews, and in and of themselves they are still quite peculiar. So let’s look a little bit closer at why they appear as they do.

The modern Santa Claus was invented and popularised first by a poet and later by a cartoonist (Clement Clarke Moore and Thomas Nast, both from the U.S.), in 1823 and 1863, respectively. However, the dubious credit for his present portly appearance is due to an advertising campaign for Coca-Cola in the 1930’s. Under all circumstances, the character is based on Father Christmas who became popular in England in the 17th century.

After the English Civil War, the Puritan government outlawed Christmas, which it viewed as a Catholic holiday. Their opponents, the Royalists, used the old myth of Father Christmas as a symbol of the good old days, highlighting a feast at the winter solstice.

But Father Christmas himself is modelled after the Christian saint, Saint Nicholas, from the 4th century. He lived a virtuous life in present-day Turkey and was reportedly generous and kind to paupers and children. Thus, he’d put coins in the shoes people left out for him, a tradition still alive today, and on occasion even enter through the chimney to deposit his gifts.

However, the stories about Saint Nicholas probably have their roots in traditions far older than Christianity. Shamanic traditions, as practised by nomadic peoples such as the Sami and the Lapps in Finland, the Kamchadals of Kamchatka and the Koryaks of the Russian steppes, and which exhibit many startling similarities to contemporary Christmas traditions.

A key figure for these peoples in Siberia and around the Arctic Circle was the shaman, usually male, who possessed knowledge of herbs and medicine and could journey to the netherworld as well as the higher spheres so as to interact with the entities inhabiting these realms.

In order to undertake these journeys, the shaman must first enter into a state of trance. He has several means at his disposal by which to obtain this goal, including fasting, music, song, dance, meditation and, last but not least, the ingestion of Amanita muscaria, known in English as the fly agaric or fly amanita.

This distinct (most often) red mushroom with white or yellowish warts on the cap is widespread over most of the Northern Hemisphere. It grows beneath birch and pine trees and is poisonous but not very much so. An adult human being would have to consume more than a kilo of it before approaching a lethal dose.

The active substance in the fly agaric is called muscimol, not to be confused with psilocybin, the active substance of the liberty cap and other so-called magic mushrooms. The types of intoxication derived from the two are very different. Whereas the ingestion of psilocybin often causes colourful hallucinations, dreamlike realisations, ego loss and a merging with the totality of the cosmos, the muscimol intoxication is an entirely different kettle of fish.

After ingesting muscimol one often becomes drowsy, nauseous and unwell, drifting off into a fitful slumber. But soon after, the subject jumps up, alert with all of his or her senses sharpened to an unnatural degree, possessed of superhuman strength and the power to leave the body.

An experienced shaman who knows how to control the intoxication is now free to fly around in our world and observe hidden things or go up and down the world tree to gain access to the domains above and beneath our everyday reality. Here he can reclaim lost souls, find aid for the ailing, and communicate with ancestors and the spirits.

An increasing number of researchers now support the theory that Santa Claus is an ancient reference to Siberian shamanism, a myth that has been slowly garbled as it gradually absorbed new elements from foreign cultures it came into contact with. And a lengthy list of phenomena seems to confirm it.

One of them is Santa Claus’ unique red, white and black outfit. Only one group of people in the entire world wears this outfit (not counting the impostors at the department stores in December, obviously) and that is shamans in the Arctic Circle when they are out gathering the fly agaric.

The fly agaric is oftentimes found beneath pine trees and, once picked, a handy way of drying them is to tie them on a string and hang them from the branches of a tree. Another method is to bring the mushrooms back home and dry them in one’s socks hung above the fireplace.

Hence, the tradition of the Christmas tree; the tradition, especially in Scandinavia, of draping little garlands and red glass balls and fly agarics made of wood or paper on the tree; and the tradition of hanging socks above the fireplace. In addition, claims have been made that the wrapping paper for Christmas presents used to be exclusively white tied with a red ribbon.

The tradition of giving presents itself originates with to the shaman who went from settlement to settlement handing out dried fly agaric to their inhabitants. As this took place at the coldest and darkest time of the year, it was probably a muchcherished gift.

The people to whom the shaman paid a visit lived in what is called a yurt, a large, round tent lined with reindeer pelts and with a hole in the top to let out smoke from the fireplace. There was a door, too, but since it was frequently blocked by snow during wintertime, the hole in the top (i.e., the chimney) had to be used for entering and exiting.

That is why we have the story of Santa Claus entering the house through the chimney with soot on his boots and face. Far into Victorian times, the fly agaric was used as a symbol for chimney sweeps. Many early Christmas cards were adorned with chimney sweeps and the fly agaric.

An essential part of the myth about Santa Claus is, of course, his flying sledge and eight reindeer. Sceptics have objected that none of the aforementioned people have practised harnessing reindeer to a sledge and that this element in the story of Santa Claus has been borrowed from the myth about Odin (or Wotan, as he was known farther south) and his eight-legged horse, Sleipner, in Norse mythology.

But the proponents of our theory cunningly counter this argument by claiming that this element was incorporated into the myth by druids much later on, and that the sledge should be viewed as a metaphor for the out-of-body experience the shaman seeks by way of the mushroom. And with the aid of the reindeer.

Because reindeer were and still are an integral part of life for these indigenous peoples, including their handling of the fly agaric. As mentioned before, the mushrooms are first dried, whereafter some choose to soak them in reindeer milk prior to ingestion in order to avoid the worst symptoms of poisoning.

Others, however, choose to let the reindeer consume the mushrooms which they are quite eager to do. Then one drinks the urine of the animals, thereby filtering out the worst of the poisonous substances. And now a cycle begins wherein reindeer and humans drink each other’s urine several times consecutively after consuming just a single helping of mushrooms.

Then humans and animals alike are in for a ride, so to speak. That may be the reason for Santa Claus’ flying reindeer sledge and that is perhaps why Rudolph, leader of the reindeer and immortalised in song, has a red nose. For reindeer, too, have a nose for the fly agaric, and Rudolph is equipped with one smack in the middle of his face! As a matter of fact, the competition between human and reindeer to find and consume or collect the mushrooms could be fierce at times.

Moreover, all of Santa Claus’ reindeer had names, some of which could put one in mind of the fly agaric, e.g., Donner and Blitzen (Thunder and Lightning) which are associated with rain and thus the proliferation of mushrooms, or Dancer and Dasher because, under the influence of muscimol, one is endowed with the stamina to dance or run very fast and very far. Whether or not Clement Clarke Moore, who originated the names, was conscious of their shamanistic connotations remains unclear.

Another similarity between our Christmas and the world of the shaman worth mentioning is Santa’s little helpers, known in English as the Christmas elves. Many feel tempted to conceive of them as entities or spirit helpers that the shaman contacts for advice and other forms of help during his mushroom reverie. No matter what, it’s an established fact that most cultures in the world have had a name for this phenomenon.

Also worth mentioning is the North Pole, the homestead of Santa Claus. Not only is the North Pole located within the Arctic Circle, where the nomadic peoples also roam, but it is also part of an ancient symbol known as the world tree, the cosmic axis, a concept of utmost importance in their mythology and view of the world.

The world tree is rooted in the netherworld of animal spirits and the dead and reaches its branches into the eternity of the heavens where it touches the North Star, also known as the pole star. This body can always be observed quite close to the celestial North Pole, thus making it a reliable navigation mark, just as in the spirit world.

From the branches of the world tree, we could then brachiate into the embrace of the tree of life and the tree of knowledge and immerse ourselves in the story of Adam and Eve and the serpent and the forbidden fruit, which is held by many to be either a psychoactive mushroom or the cannabis plant. But that is a somewhat longer, even more, convoluted and controversial, affair, going all the way back to ancient Mesopotamia, Babylonia and Assyria, which will have to wait for another time.